Books on History, Film and Media

Pioneer war photographer Donald Thompson arrived in Petrograd on the eve of the February Revolution of 1917. Since the outbreak of World War I, Thompson had worked on every front in Europe, shooting motion-picture footage and stills for US and British newspapers and magazines, carefully fashioning his reputation as a free spirit who defied danger, death, the elements, and the censors to get the picture. On assignment for Paramount and Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, and accompanied by correspondent Florence Harper, he traveled by steamer to China and across Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Over the next six months, as the country plunged into political and social chaos, he photographed demonstrations and street-fighting, was caught in crossfire between protesters and troops, and was arrested and thrown in jail. He traveled to Moscow and the Russian front lines.

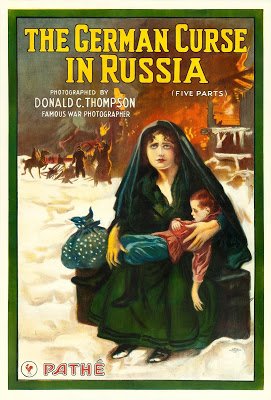

Poster for Thompson’s film, also called Bloodstained Russia, released in the US in December 1918

He met and photographed Tsar Nicolas II, political and military leaders, and prominent foreign visitors. He witnessed the power struggle between the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet, and the breakdown of discipline in the army. Donald Thompson in Russia is a compilation of letters to his wife Dorothy in Topeka, Kansas, illustrated with photos. First published in 1918, it outlines Thompson’s conspiracy thesis that “German intrigue, working among the unthinking masses, has brought Russia to her present woeful condition.” I have added an introduction and extensive notes to the republished edition (Bloomington, IN: Slavica Publishers, 2018).

In neighborhoods, schools, community centers, and workplaces, people are using oral history to capture and collect the kinds of stories that the history books and the media tend to overlook: stories of personal struggle and hope, of war and peace, of family and friends, of beliefs, traditions, and values—the stories of our lives.

Catching Stories: A Practical Guide to Oral History is a clear and comprehensive introduction for those with little or no experience in planning or undertaking oral history projects. Opening with the key question, “Why do oral history?” the guide outlines the stages of a project from idea to final product—planning and research, the interviewing process, basic technical principles, and audio and video recording techniques. The guide covers interview transcribing, ethical and legal issues, archiving, funding sources, and sharing oral history with audiences.

Intended for teachers, students, librarians, local historians, and volunteers as well as individuals, Catching Stories is the place to start for anyone who wants to document the memories and collect the stories of community or family.

READ CHAPTER 1, "WHY DO ORAL HISTORY?"

FOR REVIEWS AND DOWNLOADABLE ORAL HISTORY FORMS, SEE CATCHING STORIES.

“Budding oral historians will discover thoughtful discussion, examples, and basic guidelines for projects. The book is geared toward organizing and directing a project, and it is suitable for hands-on volunteer or student workshops.” National Genealogical Society Quarterly

“(A)n outstanding new edition for novice oral historians looking to conduct oral-history projects.” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society

“The conversational tone of the text will make it an ideal accompaniment for workshops geared towards local historical societies, libraries, and schools with high aspirations but limited resources.” International Oral History Association Newsletter

"A first-rate primer that will meet the needs of individuals seeking a practical introduction to oral history.…The book is especially well tailored to individuals working in historical societies, archives, or community organizations seeking to organize an oral history project of almost any scope.…I suspect that Catching Stories will become a popular choice for historical societies and other community organizations interested in a solid, practical guide to oral history.” The Public Historian.

Paperback 232 pages, $15.16. Order from Amazon or Swallow Press.

There is a growing need to understand how journalism continues to be practiced around the world from those who practice and teach the craft. Global Journalism Practice and New Media Performance provides an overview of new and traditional media in their political, economic and cultural contexts while exploring the role of journalism practice and media education. The authors examine media systems in 16 countries: Armenia, China, Colombia, El Salvador, Ghana, Guyana, India, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Palestine, Russia, Suriname, Taiwan, Turkey, United States, and Yemen. The case studies relate performance and output within the framework of journalism's core values and its obligations for independence, responsibility, accuracy and truth, as well as monitoring powerful state actors in the sociopolitical and economic arenas.

"Global Journalism Practice ... demonstrates that global journalism is more than just a buzzword. Instead it is about ... how journalists and journalism/media educators view journalism practice in their own countries as well as its interaction with new media technologies and socio-political and economic situations." Sara Namusoga, African Journalism Studies.

Read the back story to the editing process in my essay for Times Higher Education, "Cast Adrift: An Adventure in Academic Editing" (June 18, 2014)

From the introduction: When I took on the assignment in early 2013, it sounded like a worthwhile, intellectually stimulating project that would broaden my knowledge of current research on journalism and media around the world. Now, almost 18 months later, I and my co-editor Yusuf Kalyango, Jr, associate professor of journalism at Ohio University, feel as if we’ve been cast adrift, bobbing around in a sea of hazardous research, murky theory and citations that sting and bite. We finally staggered ashore—a month or so after the publisher’s absolute-definite-final-non-negotiable manuscript deadline. We nonchalantly described our voyage to colleagues as challenging, demanding or testing. It would have been much too embarrassing to admit that there were times when we didn’t think we’d make it. Read more.

Routledge Library Editions: The First World War. World War One was the first conflict in which film became a significant instrument of propaganda. This study, based primarily on research in the motion picture trade press, starts by examining the background to the war for the movie industry—the coverage of previous conflicts and the growth of the newsreel. It examines the experiences of American cameramen who worked in the war zone: their efforts to gain access to the front, to overcome problems ranging from unreliable equipment to poor lighting conditions to evading censorship, and how this shaped the coverage of the war. The demands of the box office led to wildly imaginative publicity claims and unethical practices: lacking genuine footage, photographers faked or re-staged scenes. News film became an instrument of propaganda: Britain Prepared engaged The Fighting Germans on movie screens. After the U.S. entered the war in 1917, film sanctified the Allied cause, downplaying military setbacks and urging patriotic citizens to buy Liberty Bonds. Although technology has changed, the issues raised by film in World War One have been mirrored in every major conflict in the 20th and 21st centuries.

See World War One Newsfilm for a description of my research.

Dividing Lines: Canals, Railroads and Urban Rivalry in Ohio's Hocking Valley, 1825-1875 (Wright State University Press/University Publishing Association, 1994)

From the launching of Ohio’s canal-building program in the 1820’s to the intense railroad promotion and speculation before the Civil War, politics, urban rivalries and the ambitions of East Coast capitalists shaped the transportation map of southeastern Ohio. The study examines the political, social and cultural dimensions of the transportation revolution, showing how the canal and railroad contributed to popular symbols of progress, nature and national unity.

{I]mpressively explains local urban and transportation history, not as a continuous process of development, but as a series of initiatives affected by the shifting interaction...between local residents and regional and national systems. Journal of American History