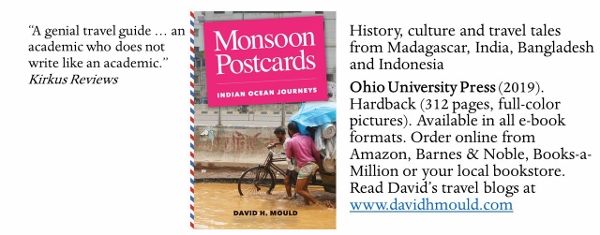

Since the Mughal period, Barisal, on the west bank of the Kirtankhola, a distributary of the Lower Meghna, has been an important port. The commercial gateway to the southwest delta, Barisal has been described as the “Venice of Bengal” or “Venice of the East,” although if you’re just counting waterways, almost any large town in southwestern Bangladesh is a Venice.

The Kirtankhola channel is not deep enough for the ocean-going cargo ships that steam up the Lower Meghna from the Bay of Bengal, but it can handle smaller freighters that ply between the towns of the delta region, carrying bricks, building materials and bulk agricultural produce. Motorized nouka deliver fruit, vegetables and fish to villages, and ferry passengers, bicycles and animals across the rivers; the catamaran version—two nouka with a wooden platform—is large enough to carry a couple of vehicles. There’s a new road bridge across the Kirtankhola at Barisal, but most rivers and channels are not bridged, and ferries are the only way to avoid a long journey on dirt roads.

I had flown to Barisal from Dhaka but decided to take the boat back. After meetings at the local university and medical college, my UNICEF host, Sanjit Kumar Das, took me home to his apartment to meet his family. His wife had not only prepared desserts but made up snacks for my return trip to Dhaka. Sanjit had booked me on the 3:00 p.m. Green Line Waterways launch. “You’ll be on the launch for at least seven hours,” he said. “You can buy food on board, but this will keep you going.”

In the Bangla transportation vocabulary, the English word “launch,” derived from the Spanish lancha (barge), is not what you’d expect—one of those sleek party boats that line marinas in Florida, or the kind of patrol boat the coastguard and police use to chase drug runners. The Bangladesh “launch,” often four decks high, carries several hundred passengers, and sometimes vehicles and cargo. One type looks like a modern ferry—the kind you’d take across the English Channel, but without the drunken football fans in the bar—while another looks like a Mississippi sternwheeler, all open decks and verandahs but without the stern wheel. From Dhaka’s Sadarghat ferry terminal, launches to southern destinations—Khulna, Barisal, Patuakhali and islands of the delta—leave in the early evening, and offer comfortable cabins with air conditioning. I haven’t done the trip this way, but travelers tell me it’s exhilarating to leave behind the noise and pollution of the capital and float off into the sunset.

At the Barisal ghat, Sanjit and his daughter guided me through the stalls selling street food, snacks, fruit and vegetables. Three launches were moored, and Sanjit wanted to make sure I boarded the right one. I stood on the top deck and waved goodbye. Below me, nouka glided in and out of the ghat, carrying passengers, bicycles, motorbikes, yellow water barrels and fruit and vegetables. Small boys jumped into the water, splashed around and climbed back up the wooden pillars supporting the quay.

A man emerged from the launch’s kitchen and laid a long blue rug on the open deck. Passengers would need to pray during the trip. I wondered if someone with a compass or a smart phone was appointed to adjust the arrow to Mecca to the meanders on the river.

After several blasts from the launch’s horn, we cast off. For an hour or so, I stood on the open deck enjoying the breeze and watching life on the Kirtankhola—the shore line of coconut palms, bananas, mango trees and small settlements, fishermen casting their nets, cattle grazing on low, grassy islands. We passed small freighters heading downstream with loads of gravel, bricks and sand, and nouka crossing the river. After two hours, we joined the Lower Meghna and the shoreline disappeared into the late afternoon haze. There wasn’t much to look at except for larger cargo ships and swooping seagulls, so I retreated to the air-conditioned upper deck. It was a midweek departure, so I had my choice of seats. A steward brought me tea and I settled down to read a book and make some travel notes.

It was difficult to concentrate because of the constant chatter from the TV monitors, occasionally interrupted by gun shots and car crashes. Green TV was offering a steady stream of Bangla-language movies with routine plots and stock characters. The Dhallywood (Dhaka-based) movie industry is not as large or well renowned as its Indian big brother, Bollywood, but it has perfected the mass production process, churning out hundreds of movies a year for domestic audiences and the Bangladeshi diaspora in the Middle East, Malaysia and the UK. There were shoot-outs on city streets, car chases, and love scenes on beaches and green mountain pastures, the characters’ slow-motion passions enhanced by rain, mist and other artificial weather elements. Most characters appeared to change clothes every couple of minutes, the women dressed in bright colors, the men with slicked black hair usually dressed in smart suits and sporting sunglasses, even during night scenes.

It was night by the time we reached the Buriganga River, the channel of the Padma that flows through Dhaka. We passed overnight launches heading south, their deck lights illuminating them against the dark water. Many passengers were on deck, enjoying the cool night air. We docked at Sadarghat, and I emerged into the maze of Old Dhaka, the streets crowded with auto-rickshaws, trucks, buses and people. I was already missing the river.